Chairman + CEO:

Reformers are pushing harder for a division of responsibilities, and here’s one company where it may be working. But don’t expect many chief executives to like it.

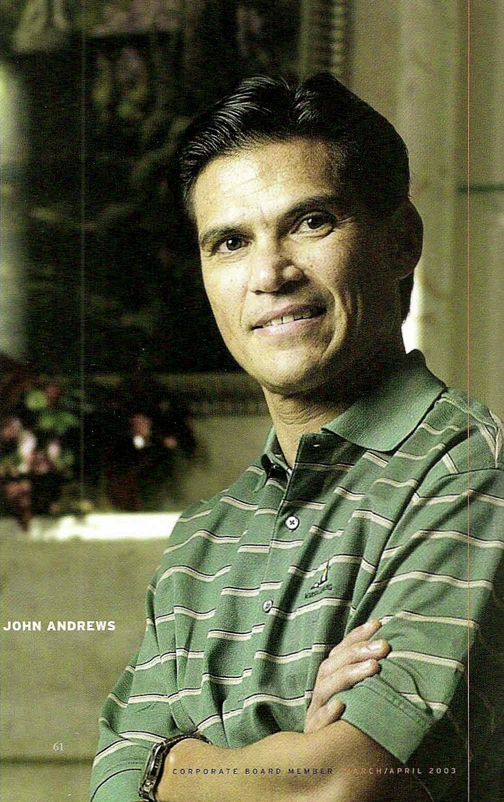

Harried CEOs can sometimes welcome partners who help shoulder the corporate burden. Just ask John Andrews, the newly hired chief executive of Giga Information Group, a young information-technology company struggling through its first brush with a weak economy. The Cambridge, Massachusetts, research and consulting outfit recently reported its fifth consecutive quarter of profitability but it’s also battling declining revenues and struggling to hold on ro customers. Its client-retention rate was 70% at the end of the third quarter of 2002, down from 79% a quarter earlier. “My job is to innovate and grow the top-line profitability,” Andrews said in late

November, four weeks into his assignment. “It’s still too early for me to tell you how I’m going to do that.”

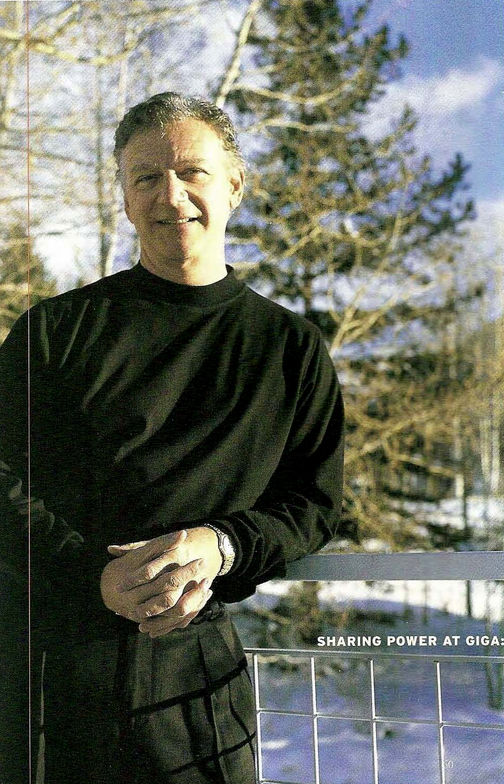

What Andrews doesn’t have to worry about is simultaneously guiding the company’s board of directors: setting its agenda, making the phone calls required to keep board members up to speed on unfolding developments, and ensuring that the board complies with all the new corporate governance rules handed down by Congress, federal regulators, and the stock exchanges. At Giga, those responsibilities rest with the non-executive chairman, Richard Crandall.

Despite some initial apprehension, Andrews now appreciates the sharing of power. “Given the current climate, this is just one less issue I have to deal with,” he says. “It’s all about maximizing time, and dealing with the board and current legislation can burn a lot of time. As long as you have a unity of interest at the board level, and especially in the relationship between the CEO and the chairman, I think this arrangement can be very beneficial.”

Many corporate governance experts have long argued that having a non-executive chairman makes sense, saying that executives who hold both posts can’t be expected to monitor their own performance effectively.

Sharing Power at GIGA: CHAIRMAN RICHARD CRANDALL…

Two Jobs, Two People

by Randy Myers

The recent rash of accounting scandals has injected new vigor into that argument. “The jobs ought to be split,” insists D. Quinn Mills. a professor of business administration at Harvard Business School. “CEOs in large American publicly held corporations have too much power; that’s the core of the abuses that have been going on. You have to reduce the power of the CEO, and one of the very few ways to do that is to separate the chairman-of-the-board position from the CEO position.”

At some companies, a lead director fulfills this kind of role. He speaks for the outside directors, and often serves as their point man in times of board dissent. An independent chairman has more authority. He presides over the full board, including inside members, and is responsible for setting its agenda. Otherwise, the differences between a lead direcror and an independent chairman are pretty much what a board says they are.

Needless to say, splitting the top jobs hasn’t been widely embraced by executives who already hold both titles. Consider the scene witnessed recently by executive recruiter Kerry Moynihan, managing partner in charge of the Christian & Timbers office in Tysons Corner, Virginia: The chairman and CEO of a multibillion-dollar public company, addressing members of his executive team, promised that no such division of duties would happen on his warth. “It’s a term of my contract,” Moynihan recalls him saying. “If I’m no longer chairman, I’m out of here.”

Many CEOs worry that reporting to a non-executive chairman would hinder their effectiveness. “The argument could be made that under the European model of splitting the two jobs, companies tend not to move as quickly or be as decisive as under the American model, where the power is concentrated in one person,” Moynihan concedes. “I also think there’s a perception in the corner office that what you may gain, theoretically,in corporate governance you will more than trade off in flexibility and responsiveness to changes in market conditions. ”

…and CEO John Andrews

Opponents of splitting the jobs also claim that history is on their side. David Dorman, the newly named chairman and chief executive of AT&T, recently told the Financial Times that while he favors an “aggressive, interactive board” to keep CEO power in check, combining the chairman and CEO jobs is a corporate governance style that has worked well for a long time in the U.S. He cited former General Electric head Jack Welch and International Business Machines’ Lou Gerstner as role models for the combined job.

D. Quinn Mills of Harvard doesn’t buy the “we’ve always done it this way” argument. “I’m prepared to take the position that in proper hands, consolidating the power can be very effective,” he says. “It’s kind of a leader system, in the sense of a military system.” The troops, in that model, always know who’s in charge. “But,” he adds, “that system has been abused on such a scale in the U.S. in the past sevetal years that investors really can’t be expected to trust it.”

CONSOLIDATING THE POWER OF CHAIRMAN AND CEO “HAS BEEN ABUSED ON SUCH A SCALE THAT INVESTORS REALLY CAN’T BE EXPECTED TO TRUST IT.”

In fact, the split arrangement often works well, not just in Europe, where it’s the norm, but also in the U.S. Intel, General Motors, and Microsoft are among hundreds of U.S. corporations, including about one-quarter of the companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index, that currently divide the two jobs between two different people. Ofcourse, many of those companies have separated the positions not so much for corporate governance reasons but as a way to help ease veteran CEOs into retirement or to accommodate their personal interests. At Microsoft, for example, founder Bill Gates tapped longtime lieutenant Steve Ballmer to serve as his CEO beginning in January 2000, so that Gates, who remained chairman, could spend less time on dayto-day management and more time functioning as the company’s “chief software architect.” At General Motors, chairman John F. Smith Jr. gave up the CEO post to G. Richard Wagoner Jr. in 2000 as a way of fulfilling long-held plans to retire between the ages of 60 and 62. More recently, Smith has announced that he’ll retire as chairman in April, when he’ll be 65. GM’s board has said that Wagoner will get the chairmanship. Other boards have separated the CEO and chairman jobs when the founder of a flashy start-up didn’t have the management experience to serve as CEO or because a family-controlled business valued the experience and expertise that an outsider could bring ro corporate captaincy (see rhe box on page 65).

Many directors are warming to the idea of splitting the CEO and chairman positions as a route to better corporate governance. In a survey of 200 U.S. corporate board members conducted last Ocrober by The McKinsey Quarterly, a journal published by management consultant McKinsey & Co., 69% favored dividing the two jobs. When Christian & Timbers polled visitors to its website on the same question in mid-November, 86% of the respondents backed the idea. “Now, 86% saying they favor it doesn’t mean that 86% of them will vote for it if a vote is called tomorrow,” cautions Moynihan. “But this will lead to pressure over time for change. And I suppose If we have another WorldCom or Enron, you’re going to see a lot more boards actually making a motion and calling a vote on it.”

Giga opted to split the jobs after its then-chairman, president, and CEO. Robert Weiler, announced last August that he was leaving to become CEO of a software company. Longtime Giga board member Richard Crandall recalls that he and his fellow directors had already been in discussions about how to make the board more independent, and separaring the top jobs seemed like a step in the right direction. As the newly elected chairman, one of Crandall’s first tasks was to head the search for a new CEO, a process that led him to Andrews. who was serving as CEO of a small private company. Before that, Andrews had worked for three years as chairman and CEO of eMedSoft.com, a publicly held health-services and technology company now known as Med Diversified.

THE COMPANY’S DECISION NOT TO OFFER THE CHAIRMAN POSITION TO ITS NEW CEO DIDN’T APPEAR TO HINDER ITS SEARCH.

Crandall says that somewhat to his surprise, Giga’s decision not to offer the chairman position to its new CEO didn’t appear to hinder its search. “I don’t know whether that was because everybody’s getting educated on board governance or people are just really happy to have job opportunities, but it wasn’t a problem,” he says.

The arrangement has been in place for only a few months, but both Crandall and Andrews say they’re pleased with how it’s working. Though Andrews doesn’t set the board agenda, he says, he has ample opportunity to work with Crandall in shaping it, and he believes that he has just as much ability to influence the company’s direction as he would if he were both chairman and CEO. For his part, Crandall says he’s been struck by how much more time he spends on Giga now that he serves as non-executive chairman. “I think about the company more; I think about things proacrively. And to me that’s the most important difference-to have one other person on the board, Other than the CEO, who is giving additional thought to the company,” he says.

Still, Crandall doesn’t expect the election of non-executive chairmen to become the norm at U.S. companies soon. “In general, CEOs feel, or at least have in the past, that getting ‘Chairman’ added to their title is a recognition of their worth and a promotion,” he says. “As long as that’s the case, there’s going to be a tension-a feeling that they’re not full CEOs until they’re chairmen. That thinking has to change in order for this concept to become a permanent new direcrion in corporate governance.” With increasing pressure from institutional and private investors, and perhaps with leverage from government overseers as well, that thinking could change faster than power-obsessed CEOs now suspect.

To comment on this story, please e-mail edltor@boardmember.com.

CORPORATE BOARD MEMBER MARCH/APRIL 2003