by Rick Crandall

Revised October, 2016

Almost everyone knows what a geyser is and many have seen the famous one at Yellowstone. A much lesser-known man-made invention operating on a similar principle is an automatic table-top fountain that cleverly seems to defy gravity by operating even without the heat source that underlies a natural geyser.

Old Faithful, California

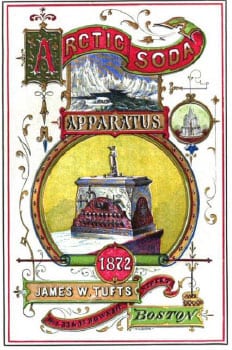

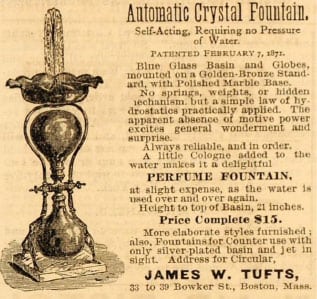

The Automatic Crystal Fountain, was commercialized in the U.S. by James W. Tufts in about 1871 as a novel new product released by his company, the Arctic Soda Apparatus of Boston, Massachusetts.

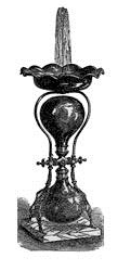

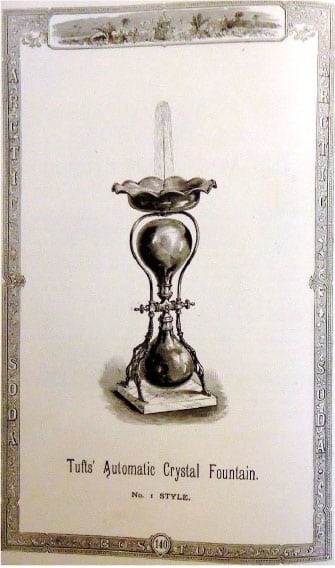

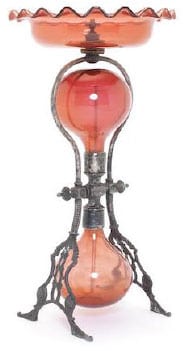

The Automatic Crystal Fountain was a product series, beautiful in appearance and magical in operation. Tuft’s catalog of 1873 advertised it as “… substantial and simple, with no weights, springs, leaky cylinders or complicated arrangement of any kind.” It needs no power source. A mere inversion of the globes results in an 8” fountain-type spray of water above the globes, which lasts for 15 minutes. A flip of the globes starts the fountain for another interval.

Tufts Automatic Crystal Fountain; Crandall collection

One purpose of the fountain, in addition to being attention-getting by seemingly making “water run uphill,” was as an air perfumer. By scenting the water with an essential oil, the fountain could spread a delicate fragrance in a room. The suggested oils, available at any apothecary, were bergamot, cologne, lemon, bay, cinnamon, lavender, citronella, rose, orange, jasmine and verbena.

Directions for perfuming the water read: “Take 1 teaspoonful of essential oils, mix thoroughly in a glass dish with 1 ounce of carbonate magnesia; then add gradually 3 quarts of water; shake the whole together in a bottle, and filter through filtering paper.”

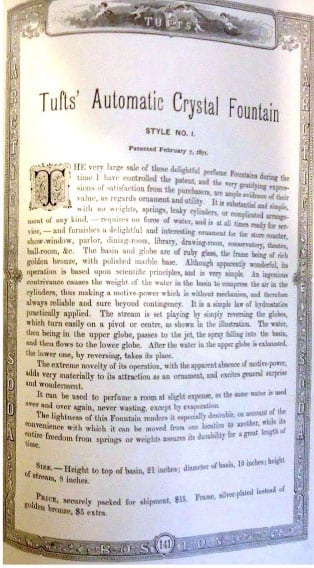

From the Tufts’ 1871 catalog: “The very large sale of these delightful perfume fountains during the time I have controlled the patent… are simple evidence of their value …. The basin and globe are of ruby glass, the frame being of rich golden bronze, with polished marble base. Although wonderful, its operation is based upon scientific principles…An ingenious contrivance causes the weight of the water in the basin to compress the air in the cylinders, thus making the motive power which is without mechanism. It is a simple law of hydrostatics practically applied. The extreme novelty of its operation, with the apparent absence of motive-power, ads very materially to its attraction as an ornament, and excites general surprise and wonderment.”

Perpetual table fountains were highly ornamental novelties intended for the mansions and emporiums of an ostentatious time. Following the depression of 1893, Tufts, in his “Letter to the Trade,” quoted Motley, the historian, who wrote “Give us the luxuries of life, and we will do without the necessities.”

Table fountains certainly qualified as luxuries. The least expensive Tufts version cost $15, which represented more than two weeks’ pay for a typical laborer of the period. “Ruby Glass, Etched” fountains were listed for $20-30.

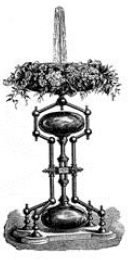

In one of his catalogs, Tufts also offered a second, more elaborate and expensive parlor fountain, designated “Style No. 2,” which sold for a staggering $50. Only one surviving example of Style No. 2 is known. The catalog description states that the fountain “has two basins, the upper one is the reservoir for water which supplies the Fountain and the lower is for flowers, but instead this may be used for gold fish with beautiful effect.”

Fountain illustrations from the circa 1877 Tufts trade catalog

OPERATION

But how did it work? With no springs, pumps or external mechanism of any kind, the fountain was designed to shoot a jet of water 6 – 8″ into the air from a nozzle mounted in the center of the glass basin. This was the time it took all the water in the raised globe to move through a valve at the intersection of the globes, up one side of the fountain’s tube-like frame, out the nozzle as a spray, and then down through the frame from a drain hole in the basin to the lower globe. Rotating the globes restarts the fountain.

Tufts’ instructions state explicitly that the fountain must be filled by pouring water into the glass basin. This is because the fountain’s motive power comes from air pressure generated by the weight of the water held in the basin.

Geysers operate via this mechanism. While the fountain requires that the air supply container be manually emptied of water, geysers have an analogous “air-supply container” that is steadily heated by geothermal energy. When the water level in the air-supply container becomes too high, the geothermal heat causes the water to boil off and therefore naturally empties the container of water and replaces it with water vapor instead of air.

Emblem: Pat. Feb 7, 1871 J.W. Tufts Boston

MARKETING

Tufts marketed his fountains from the mid 1870s until the 1890s. Most of the existing examples are American, made by Tufts. The earliest ads are from the 1876 Crockery and Glass Journal referring to it as an “Automatic Crystal Fountain.’’

Close-up of rotation detail and fountain “geyser”

Crandall collection

Tufts noted in a circa 1877 trade catalog now in the Rare Books Department at Boston Public Library that “when perfume is added to the water, the fountain can serve as an air purifier ideal for sick rooms. It also would make an attractive ornament for the store counter, show-window, parlor, dining room, library, drawing room, conservatory, theatre, ball room, etc.”

The glass was available in opaque white, plain or with enameling or gilding, colorless, blue or ruby glass all with or without acid-etched decoration. The bases were square white Italian marble or Seveir marble with molded edges. The frames were golden bronze antique bronze silver-plate or fancy gold. So far there are eight in museum and private collections in the United States and several more have come up for auction.

Examples of a Tufts ad and catalog frontispieces, the latter illustrating his penchant for fancy designs

Tufts catalog description of the Style 1 fountain

INVENTION

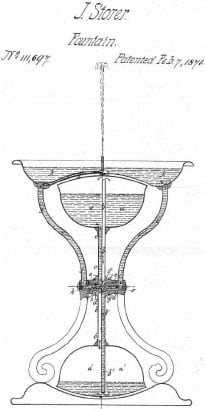

James Tufts didn’t actually invent the Fountain. He purchased the patent rights from Joseph Storer of Houndsditch, England whose patents were issued first in England in 1870 and then in France and the U.S. in 1871.

On June 7, 1870 Storer obtained Patent No. 1647 from the English patent office for an “improvement in Fountains” he declared the nature of the invention to be an improvement in that class of self-acting fountain known as Heron’s fountain, and that his patent:

‘Relates to the application of means whereby the repeated filling and emptying of the cisterns or reservoirs is obviated. ‘

Storer described the two cisterns and their connecting pipes and went on:

“To put the fountain in operation water is poured into the dish or basin until the lower reservoir is filed and the opening is covered. The cisterns are then turned on their axis of motion, so as to place the filled one at the top and the water will flow to a level in the jet pipe and be forced up to the nozzle from which is falls back into the basin and drains down into the lower cistern. When the water has flowed through, a reversal of the resolving cisterns will cause it to start again.”

He then patented the fountain in the U.S. receiving Patent No. 111,697 on February 7, 1871. The text and the illustrations of the American patent are identical to the London one.

HERON’S FOUNTAIN

Heron of Alexandria in his Pneumatics of about AD 62 described the water-fountain which operated with air pressure and this was illustrated with drawings in several 19th century encyclopedias.

Heron’s fountain is a hydraulic machine invented by the 1st century AD inventor, mathematician, and physicist. Also known as Heron of Alexandria. Heron studied the pressure of air and steam, described the first steam engine, built toys that would spurt water, and a fountain. Various versions of Heron’s fountain are used today in physics classes as a demonstration of principles of hydraulics and pneumatics.

Illustration from Knight’s American Mechanical Dictionary (Boston: Houghton, Osgood & Co., 1880, p. 910), showing the principle of the fountain’s operation as first described by the ancient mathematician and engineer Heron of Alexandria (c.10-70 AD)

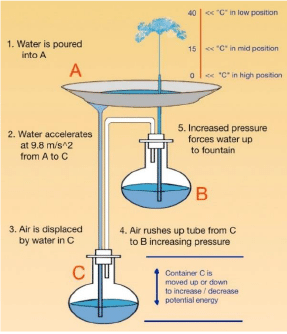

Heron’s fountain is built as follows:

- Start with a basin (A), open to the air. Run a pipe from a hole in the bottom of that basin (A) to an airtight air supply container (C).

- Run another pipe from the top of the air supply container (C) up to nearly the top of the airtight water supply container (B).

- A pipe should run from almost the bottom of the water supply container (B), up through the bottom of the basin (A) to a height just above the basin’s rim and becomes the spout. The fountain will jet upwards through this pipe.

Operation:

- To prepare for start, the air supply container (C) should contain only air; the water supply container (B) should contain only water.

- To start, pour water into the basin (A).

- The water from the basin (A) flows by gravity into the air supply container (C). This water forces the air in (C) to move into the water supply container (B), where the increased air pressure forces the water in (B) to jet out the top as a fountain into the basin (A). The fountain water caught in the basin (A) will drain back to the air supply container (C).

- The flow will stop when the water supply container (B) is empty.

Heron’s fountain is not a perpetual motion machine. If the nozzle of the spout is narrow, it may play for several minutes, but it eventually comes to a stop. The water coming out of the spout goes higher than the level in the containers, but the net flow of water is downward. If, however, the volumes of the air-supply and water-supply containers are designed to be much larger than the volume of the basin, with the nozzle of the spout being narrow, the fountain can operate for a far greater time interval.

The fountain can jet almost as high above the upper container as the water falls from the basin into the lower container. For maximum effect, place the upper container as closely beneath the basin as possible and place the lower container a long way beneath both.

EUROPEAN AUTOMATIC FOUNTAINS

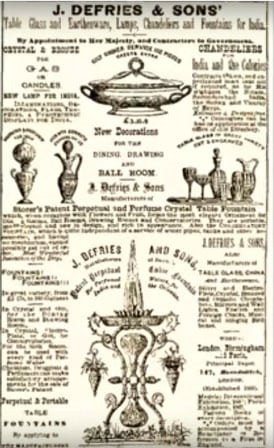

There is evidence that these fountains were also made in Europe, at least by J. Defries & Sons in the UK based on the Storer patent. Examples can be found with brass plates that say: “J. Defries & Sons, Manufacturers of Storer’s Perpetual Fountain, 147 Houndsditch LONDON.”

It is likely therefore, that Tufts purchased just the U.S. or North American rights to the patents and others proceeded to make fountains under license or purchase of rights from Storer for European markets.

Here is a Defries fountain that looks nearly identical to the Tufts design, perhaps even imported from Tufts.

Here is an all-metal Defries fountain with a plate that says: “J. Defries & Co. Manufacturer of Storer Patented Perpetual Fountain 147 Houndsditch LONDON”

AN EXTRAORDINARY AUTOMATIC FOUNTAIN

In response to a Heritage Auctions cataloguer having Googled and finding an earlier version of this article, I was contacted seeking any additional information on this amazing example of a perpetual fountain they had up for auction. This incredibly elaborate, silver-plated fountain has a plate stating “Storer’s Patent” which could mean it was made in Europe but the absence of Defries notation would indicate it was not made by Defries. It could possibly have been made by Tufts since he produced many silver-plated designs for silverware, but an assessment of the four dragons point towards a made-in-England assessment.

This is by far the fanciest example of an automatic fountain surfaced to date. I couldn’t resist.

The auctioneer offered that this came from a wealthy family, resident in Texas, who originally purchased it at an antique shop.

Heritage Auction (Dallas, TX) description:

“The fountain surmounted by nozzle and cut-glass bowl, below to hourglass shaped frame embellished with beadwork, figural dragon mounts, scrolled foliage, and rosettes, conforming hourglass-shaped water tanks, two cut-glass bowls suspended on frames hanging from dragon’s mouths, lower frame with exaggerated dragon mounts to sides of rocky base encasing round mirror.”

THE DRAGONS

No less than four dragons appear on this Storer fountain, which may be key to its origin. The dragon design is definitely neo-Gothic (or Gothic Revival) with its spread wings and scrolling tail. Neo-gothic is a reach-back to medieval times but popularized in the latter part of the 19th century in England. From The History of Dragons in Art by William O’Connor, we learn that while dragons have a very early role in Asia, sometime after the fall of the Roman Empire the dragon took its familiar form in western civilization. The story of Adam and Eve includes the appearance of Satan in the form of a serpent, representing evil.

Storer fountain’s upper dragon holding crystal bowl on a chain.

During the Age of Reason (17th century), the western dragon became more a creature of entertainment. The dragon took on a decorative nature and was treated as a fantasy creature. The 19th century saw a resurgence of the dragon. By the second half of the 19th century the neo-isms, including neo-gothic of the beaux-arts academic style used the dragon as a decorative embellishment which is precisely how the dragons are used on this Storer fountain.

Dragon on lower leg of the Storer fountain;

Classic neo-gothic dragon design

SOME OTHER EXTANT AUTOMATIC FOUNTAIN EXAMPLES

James Walker Tufts (1835-1902)

Shortly after his father’s death 1851, James was apprenticed at sixteen years of age to the Samuel Kidder Company, an apothecary shop in Charlestown, Massachusetts. His apprenticeship lasted six years.

Shortly after completing his apprenticeship, with the advice and help from his father’s friends, he located and purchased his own drug store in Somerville, Massachusetts. He worked endlessly preparing his own cures and extracts and, four years later, was able to purchase a second store in Medford, Massachusetts. He also purchased drug stores in Winchester, Woburn, and Boston, Massachusetts, creating one of the earliest drug stores chains in the United States.

Tufts began manufacturing items for other apothecaries and, by age 27, had developed a complete line of soda-fountain supplies, including flavored extracts. Tufts was enterprising, as he also began selling silver-plated tableware. The use of silver plate, called “the everyday man’s silver.” rather than pure sterling silver meant that more people could afford to buy these items. He also started The Arctic Soda Fountain Company to manufacture his own soda fountain apparatus.

In 1891, Tuft’s Arctic Soda Fountain Company consolidated with A. D. Puffer and Sons of Boston, John Matthews of New York and Charles Lippincott of Philadelphia to become the American Soda Fountain Company with James W. Tufts as the company’s president. In 1895, when Tufts was 60, he sold his part of the business. He died in 1902 at the age of 67.

SOURCES

- Johnson, Laurence A., The Spinning Wheel, May 1961, p20.

Tufts’ Automatic Crystal Fountain - Boston Public Library, Rare Books Dept., Tufts Trade Catalog circa 1877

- Spillman, Jane Shadel, Corning Museum of Glass, Corning N.Y.

The Automatic Crystal Fountain - Wikipedia, Heron’s Fountain

- The History of Dragons in Art by William O’Connor, 2012 blog entry

- The Heritage Auction, Dallas, TX