LITERATURE DISCOVERY FROM AMERICA’S FIRST COIN-OP MUSEUM

Rick Crandall

MOST collectors of automatic music machines undoubtedly thought as I did, that we were in a field of collecting that dates back only to the 1950’s or so. Certainly it has been only a few decades, during which time published literature has become available, that restorers have developed their skills, and prices have commenced their upward movement. Who would have imagined that there would be anyone interested in collecting these items in the 1930’s since many of the later instruments were first being junked then? After all, you don’t find many people collecting electronic calculators today. When they become obsolete, they get trashed.

In the 1930’s, however, there was a visionary, a Chicago chemist by the name of Alden Scott Boyer, who saw the beauty and fascination of coin-operated entertainment devices, and who began to establish a collection. Like most modern collectors, Boyer had a regular job during the day. He was President of Boyer Chemical Laboratory Co., Inc., of Chicago and Paris.

Figure 1. Alden Scott Boyer, circa 1938.

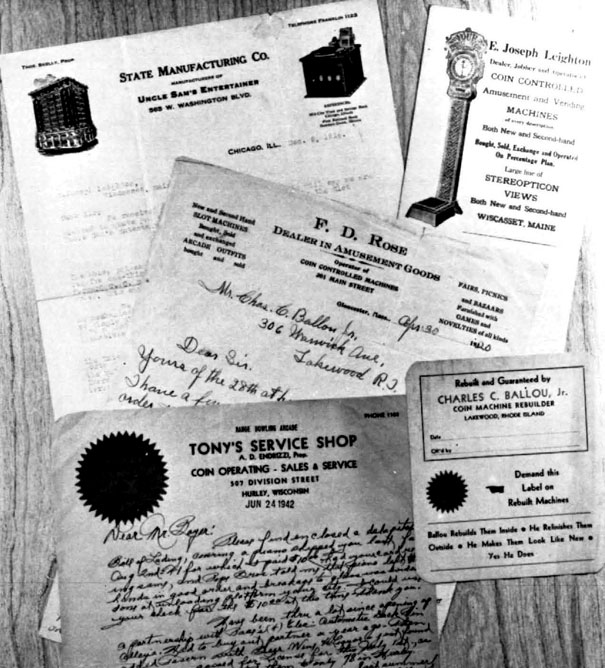

Figure 2. Assorted letterheads from contributing dealers and distributors

He already had the collector’s bug in his blood made evident by his position as President of the Chicago Coin Club for six years. He was also President of the American Numismatic Association.

One day in the year 1938, Boyer had a meeting with a man by the name of Mr. Lightner, the publisher of Automatic Age magazine. Automatic Age was a prominent national monthly magazine that had been well established since 1926, specializing in all forms of mechanical entertainment devices. Alden Boyer learned from Mr. Lightner that no one had yet established a collection of coin-op machines that was comprehensive and historically important.

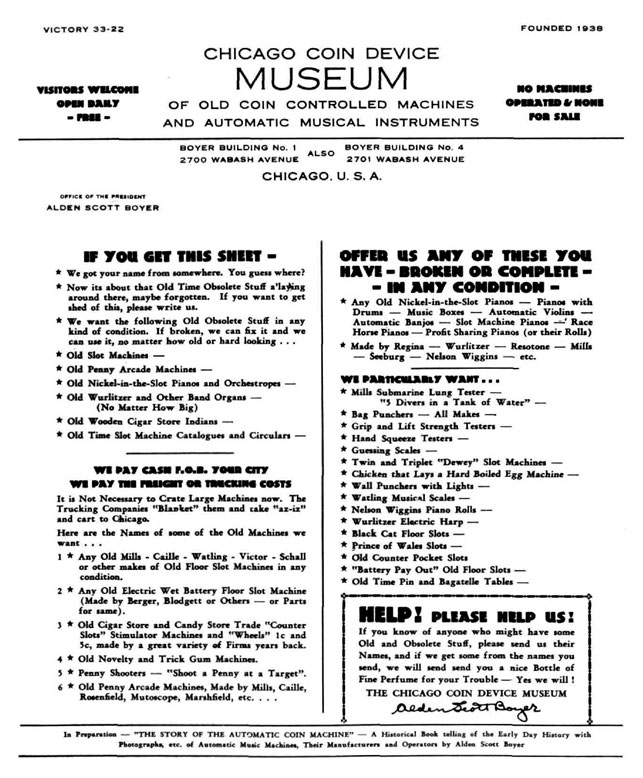

The idea caught fire in Boyer’s imagination, and in short order he had formed the Chicago Coin Device Museum housed in the Boyer Building at 2700 South Wabash Avenue in Chicago.

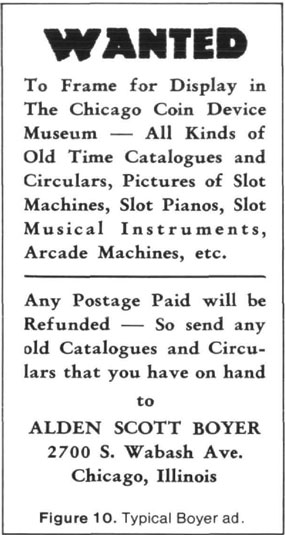

How many of us would like to turn the clock back to 1939 when Boyer was able to place a few ads asking for “… old-time slot-machines, Regina musical boxes, Mills Violanos, and slot-pianos,” and to have returns coming in from all over the country?

Figure 3. Boyer museum mailer seeking desired machines. Note that even in the 1930’s the desirability of the stringed instruments, the Encore Banjo, Mills Violano, and the Wurlitzer Harp, was sufficiently high to merit specific mention.

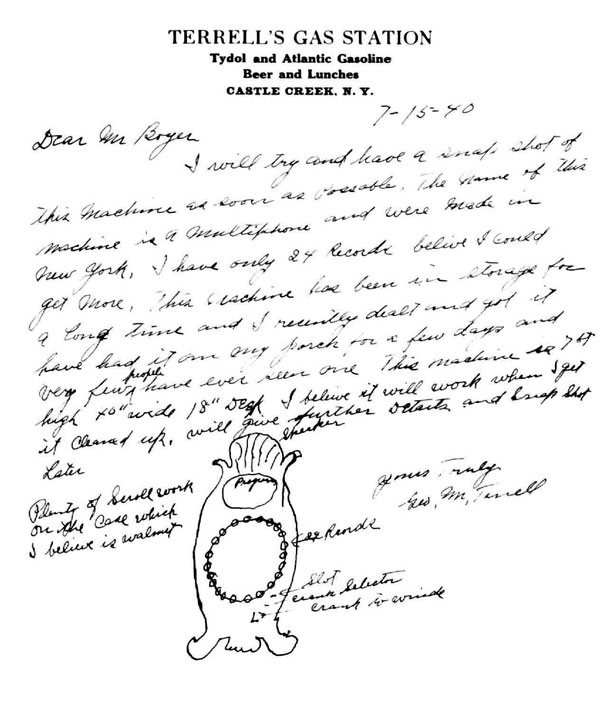

Figure 4. Letter offering 1905 “clamshell” 24-cylinder Multiphone. Wasn’t it easy then?

In two months the Boyer museum had 150 machines, including some amazing rarities. In an interview, Boyer was noted as recollecting:

Mr. McGrath of the McGrath Company of Chicago gave me a Wurlitzer piano containing a calliope [probably a misnomer for flute pipes -author] triangle and drums, an instrument that required eight men to move.

The instrument he was describing may have been the one depicted in the center of Figure 9, a Wurlitzer CX orchestra.

The interview went on:

Figure 5A. From the Boyer Museum: Seeburg KT Special with art glass removed.

Figure 5B. From the Boyer Museum. Western Electric C cabinet piano playing A rolls.

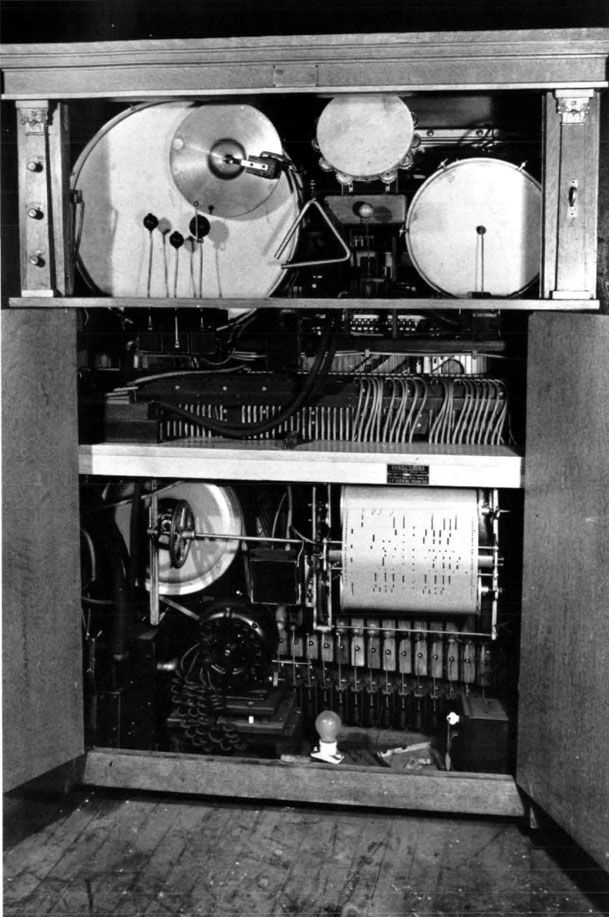

Figure 5C. From the Boyer Museum: rectangular-case Multiphone cylinder phonograph.

Joe Ancell of Chicago secured for me, at very nominal prices, a complete series of Regina music boxes and records from the earliest to the latest styles and sizes.

Charles Ballou of Lakewood, Rhode Island, sent me a line of the oldest floor slot-machines (known to collectors today as upright single-wheel gambling machines), all stunning and new. Joe Paupa [son of the Paupa of Paupa & Hochreim – Author] gave me one of the first mechanical-payout five-cent machines that his father ever made, the ‘Uncle Sam.’

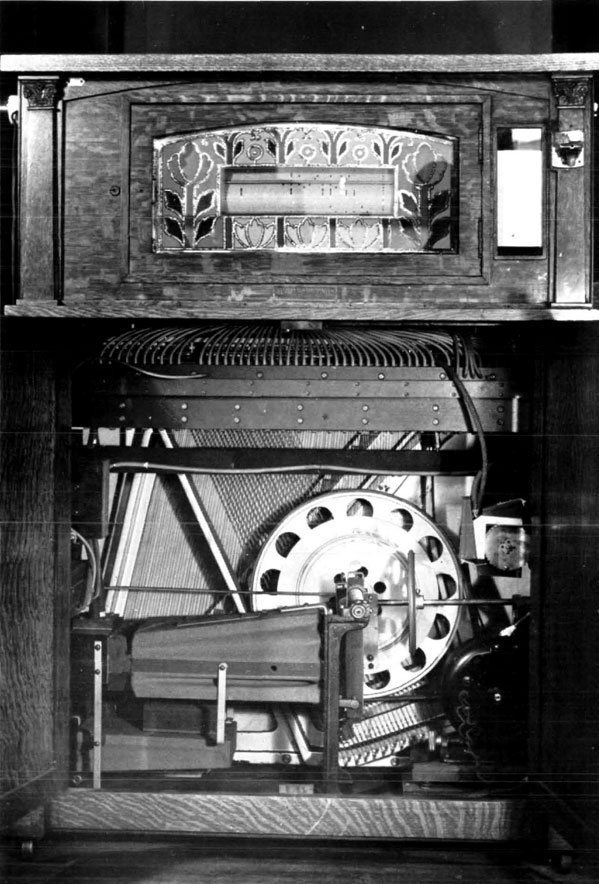

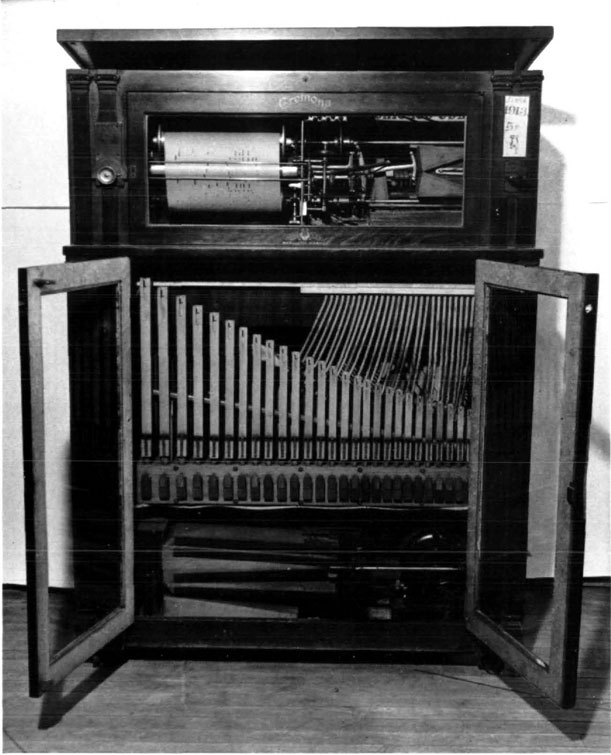

Figure 5D. Unusual Cremona cabinet machine with violin pipes and playing M rolls with special perforations to control the rare tune selector. This photo was mixed in the Boyer material, but we know from Art Reblitz that it came not from the museum but from a barber shop a few doors north of Svoboda’s.

Mr. Joseph Leighton of Wiscasset, Maine, sent me the Chicken-That-Lays-the-Hard-Boiled-Egg machine for six dollars and an aggregation of the oldest coin-machines I ever dreamed of.

Mr. Tony Endrizzi of Hurley, Wisconsin, gave me some old Silver Dollar slots from up in the wild north country, and he also sent me a Resotone slot-piano that gets its music from xylophone bars instead of piano strings.

Have you had enough? I repeat these recollections because they refer to many of the early operators with possibly undiscovered hoards that may yet surface.

An article in Automatic Age in February of 1940, said:

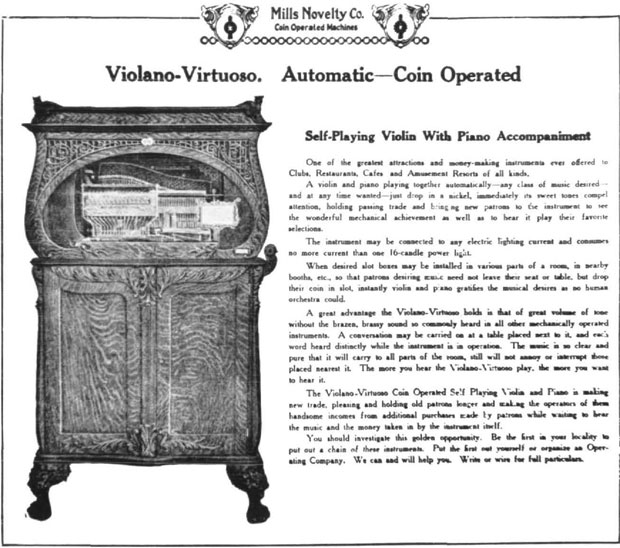

As a result of radio broadcasts regarding the Boyer collection, Mr. Boyer was able to obtain a Violano-Virtuoso with single violin and a Mills Violano with two violins and a piano.

Figure 5E. From the Boyer Museum: Mills double Violano-Virtuoso

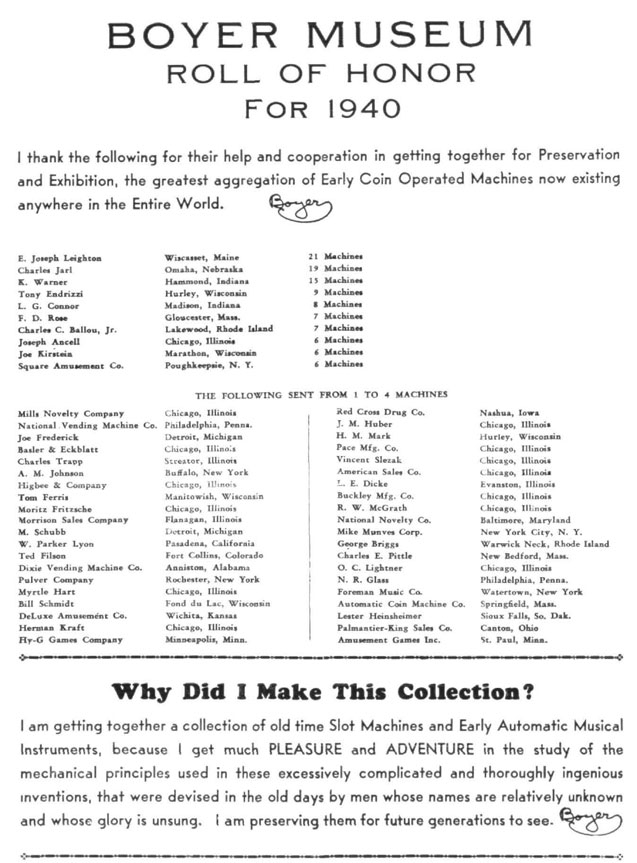

Figure 6. Boyer Museum flier acknowledging contributors. Included among the benefactors were manufacturers, distributors, and individuals. Note the unusual and sincere statement of Boyer’s motives.

Figure 7. Left to right: Caille `Centaur’ jackpot upright; Caille ‘Ben Hur’, a 1903 counter-style single-wheeler; ‘The Chicken That Lays Hard-Boiled Eggs’, ca. 1910 (the chicken cackles and vends hard-boiled eggs for a nickel); Mills ‘Brownie’ countertop payout gambling machine; Caille ‘Eclipse’ (missing top sign); Mills ’20th Century’ for silver dollars, paying from $2 to $20, a lot of money in 1901; ‘Uncle Sam’, thought to be the first of the color-wheel machines made in 1890 by the Chicago firm of Paupa and Hochreim, who sold out to Mills.

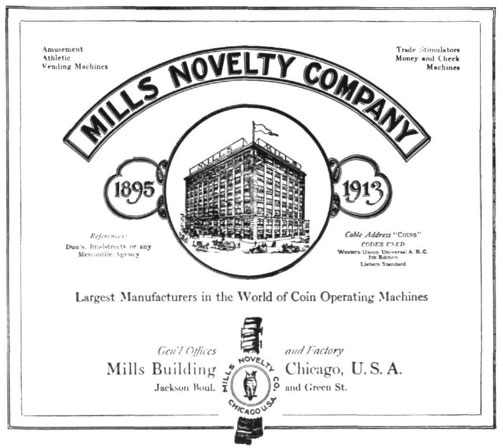

Figure 8A. A page from the 1913 Mills catalogue, one of 23 different Mills catalogues from the Boyer library.

Figure 8B. An early and extinct Bowfront Violano is shown, which differs from the Bowfront in the author’s collection in that the coin slot is on the right side (instead of the right front); cast-iron gargoyles used for legs are borrowed from the Mills 20th Century upright slot-machine of the same year; the Mills owls are cast in iron as top corners.

Alden Boyer was an eclectic collector, dividing his time between music and gambling machines and trade stimulators. His lineup of early, rare, and beautiful upright slot machines in restored condition was truly a sight to behold, as seen in the picture of just one corner of the museum, shown in Figure 7. People contributed machines with enthusiasm, and each one had a story.

Boyer recalls a Miss Myrtle Hart of Chicago, who “… gave me her mother’s Violano-Virtuoso in perfect condition, practically new, with all the sacred-music rolls that the Mills Novelty Company made especially for her mother from songs in the Old Gospel Hymn Book, the leaves from the hymnal being in each box with its roll. Miss Hart said her mother used to sing with the Violano.”

Fortunately for us all, Mr. Boyer was a true collector, with a sense of history. He not only assembled a wide sampling of machines, but he sought the associated literature as well. He was aggressive in posting ads for catalogues and circulars, and he wrote to manufacturers most of whom were still in business then.

Automatic Age comments, “The Mills Novelty Company supplied Mr. Boyer with several of their oldest catalogues, taken from their own archives, with information and illustrations that have been helpful in starting the collection.” Assembling a library of original literature from contributions directly from the manufacturers’ libraries is a luxury that is long since gone.

In fact, Boyer carefully gathered a broad selection of catalogues and advertising pieces from Mills, Regina, Wurlitzer, and others, as well as famous slot-machine companies such as Caille, Watling, and Jennings.

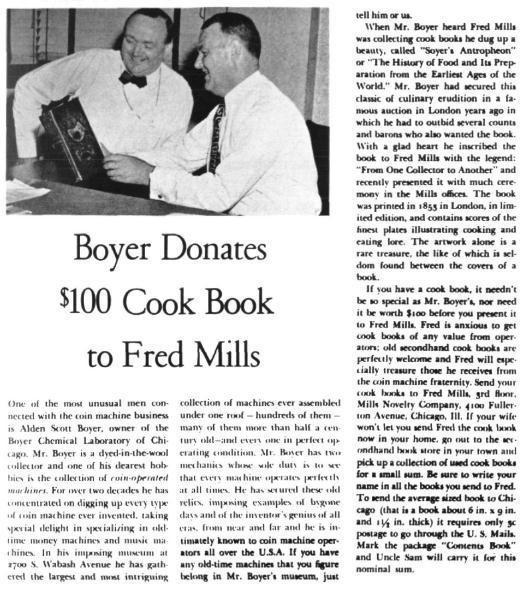

Being a Chicago resident, Boyer must have been impressed with the Mills Novelty Company. Mills was one of the oldest and largest entertain¬ment-device companies in the United States. Founded in 1895, Mills made a wide variety of repeat success in both the gambling and trade-stimulator fields as well as with automatic music-machines. Alden Boyer obviously made sure he cultivated his ground carefully, and he was successful in establishing just the relationship he wanted. His success was made clear by the article in the Mills house publication Spinning Reels, in November, 1941, which described how Boyer donated a $100 antique cookbook to Fred

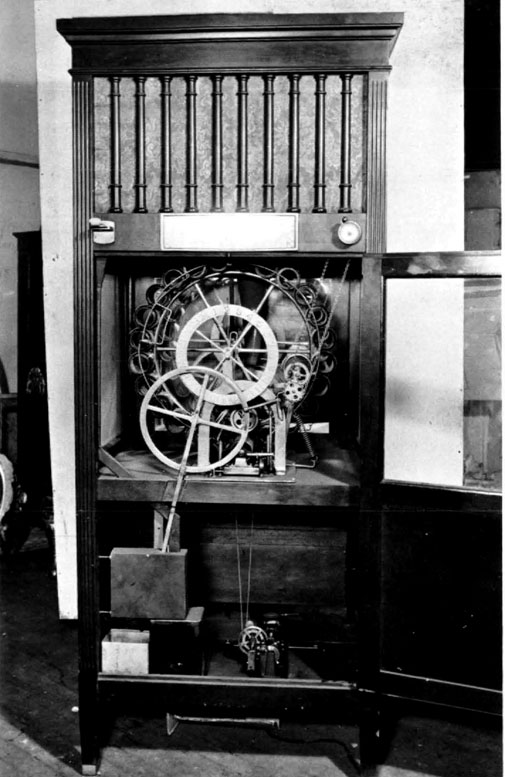

Figure 9. Left to right: Encore Banjo with 1901 New York-style earlier case, missing top crest; Wurlitzer CX orchestrion (note erroneous use of the word orchestrope, which was a model of a Capehart jukebox sold in 1928) with piano, mandolin, snare and bass drums, triangle, flute and violin pipes, xylophone, and 6-roll changer; an unusual Seeburg F, a keyboard piano with flute pipes, castanets, triangle and tambourine played by the G roll (front-mounted lamps missing); a Regina Hexaphone that made a selection from six phonograph cylinders.

Mills as a contribution to Mills’s cookbook collection. For this $100, Boyer got the article (Figure 11) printed in the Mills magazine, which went to all Mills distributors and route operators.

The museum was well appreciated and became widely known, but it was also to be short-lived. In the early 1950’s Boyer died, and the museum was disbanded. Fortunately, Chicago Heights tavern owner Al Svoboda was an acquaintance of Boyer’s and was also interested in coin-op machines. Svoboda had a loosely specified arrangement with Boyer, the result of which was the aquisition of much of the museum’s properties. Some of the Boyer machines were still together as a collection for viewing at Svoboda’s Nickelodeon Tavern as recently as 1982. Sadly, Al Svoboda’s collection is now being disbanded.

Svoboda’s was a haven for many collectors who entered the field throughout the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s. The music machines became a training ground for restorers, and many of today’s acknowledged craftsmen worked on Al’s machines.

Amid all the hoopla of setting up the Boyer machines in Al’s Tavern, the library was packed into cartons and stored in the basement. Over the years, some have visited the catacombed basement and have located pieces of the library for inclusion in various publications, most notably the Encyclopedia of Automatic Musical Instruments. Not all of it had been seen together, since the literature was scattered throughout a richness of musical boxes, gambling machines, arcade devices, parts, motors, tools, and anything else that Al had seen fit to collect and pile up in his basement.

Amazingly, most of the library came through the years unharmed. In 1980, Al and his son Corky began laying plans to sell the collection. My own interest in the machines and the associated literature was fired by the grapevine news that some of the items would be sold.

It didn’t take long to revisit Al Svoboda and retrieve a total of 3½ dusty cartons from the depths of Svoboda’s Nickelodeon Tavern. With excitement and anticipation, I began peeling back the layers of literature. At first all I could see were layers of 1940’s WLS Radio magazines, Duo-Art reproducing-piano music bulletins, and some phonograph catalogues.

Figure 11. Article on Alden Boyer and Fred Mills published in the November, 1941 issue of “Spinning Reels.”

Then real nuggets began to show in the bottom of the first carton. Almost a complete collection of Mills catalogues dating back to the late 1800’s, including color pictures of early Violanos from 1906, emerged one after the other. There was an Ogden catalogue showing a music machine I had never heard of-Automatic Chime Bells, and there was a Rosenfield catalogue showing the Illustrated Song Machine. There were over 350 pieces in all, and the condition was excellent. In no time, the cartons were purchased, transported, dusted, organized, and catalogued. It was not until then that I realized that the contents of those cartons was a carefully assembled library.

Included were many of Boyer’s letters searching for items in catalogues and deciphering dates on undated pieces. Thankfully, the literature is preserved, and once again it can help collectors shed light on the mysteries of an age that captures our imagination.

Figure 12. AI Svoboda in a 1950 promotional photo that was later made into a post card. Left to right: Seeburg KT with art glass removed and automatic figures interspersed with the triangle and castanets; Link style C with flute pipes using the RX endless-roll system; early barrel orchestra. Al himself is shown with his “zig-a-boom” that became a kind of Svaboda trademark.

Alden Scott Boyer was a true pioneer. He developed a fascination for automatic entertainment devices before they had any real value or following. His aggressiveness and sense of history undoubtedly resulted in saving an assemblage of material that would otherwise very likely have perished.

Here’s an enticing thought: If the Chicago Coin Device Museum was the first of its kind, what was the second, and where is it today?

Credit. Special thanks are due to Dave Ramey, Chicago Heights restorer and collector. Dave not only gave me early information about the existence of some literature at Svoboda’s, but was also helpful in identifying the instrumentation of some of the machines pictured in the article.